Through a Gate Darkly

Julie Eaton

You heard a foot pass, it trailed over the grass,

You shivered it came so near.

And was it the head of a man long dead

That raised itself out of the mere?1

M.R. James

The genesis for creating Light over Landsdown was a wrought-iron gate in the wall at Great Livermere Hall in Suffolk.2 Although I am from Suffolk my first visit to Great Livermere was two years ago. I stood beside the wall in this quaint and quiet place on a still winter's day, slowly becoming aware of rustling leaves the other side of the gate. Suddenly a Muntjac peered through the gate mutually holding my stare briefly before it disappeared. I did not know, at the time of this first visit, that the Hall was formerly Livermere Rectory, the family home of ghost-story writer Montague Rhodes James OM (1862 - 1936). James often signed himself and is referred to as MRJ. He set his last story 'A Vignette' (1936) at Livermere Rectory.3 In this story he describes 'an iron gate which admits to the park from the Plantation', and a 'wooden gate with a square hole' which an apparition peers through (401-4). My own encounter with a gate at Livermere Hall later on reminded me of this story, and of how one's imagination may well be sparked towards ghostly spectres.

In chapter one of this critical commentary I attempt to ascertain that a sense of place in life and fiction is vital, and, although there is plenty of scope for further studies to be written on M.R. James's life and oeuvre, I am reflecting in chapter two on MRJ and the very specific context of Suffolk and Livermere. This place inspired the writing of Landsdown; I am not attempting, however, to compare my story with MRJ's work! Instead I am reflecting on the interesting ways that place informed MRJ and concluding by briefly noting theories of ghost stories with reference to him.

M.R. James was known to friends as Monty, although his father the Reverend Herbert James affectionately called him Toby or Tobe (which I discovered after writing Light over Landsdown).4 Known as the 'learned boy' when as a scholar of Eton, he went up to King's Cambridge, his father having also attended both institutions (28). MRJ was a prodigious and brilliant antiquarian, biblical scholar and medievalist, with magisterial scholarship in catalogues and manuscript studies (Jones/Cox). He became Dean and Provost of King's College Cambridge, Director of the Fitzwilliam Museum, and Provost of Eton. He also wrote ghost stories, for which he is best known as they have proved to be enduringly popular.

The sense of place of the Suffolk landscape in MRJ's stories includes 'A Vignette' and 'The Ash Tree' (both Livermere), 'Rats' (the Suffolk coast), 'Oh, Whistle, and I'll Come to You, My Lad' (Felixstowe), 'A Warning to the Curious' (Aldeburgh) and 'The Tractate Middoth' (Bredfield/Bretfield Manor). Darryl Jones notes in his introduction to MRJ's stories that select friends retired to the Provost's rooms on Christmas Eve at King's College, Cambridge, to hear MRJ read his ghost stories by candlelight, a kind of 'sinister Christmas ritual' (ix). He describes the scene:

This is a dark, Victorian Anglicanism, practised out there on the fens in the flat east of England, where the sky and the land seem part of one another... where there is no horizon; far away from the concerns of the world. The Provost thinks of his own childhood, not far from here, a world of isolated country houses in the Italian style, of Martello towers, shingle beaches, Anglo-Saxon burial mounds, witches... (ix).

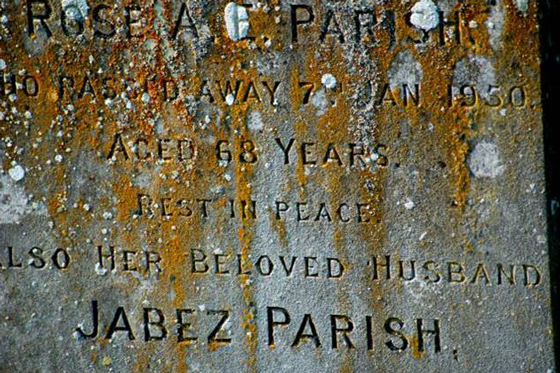

According to Michael Cox, biographer of M.R. James, MRJ's roots as a writer are within Suffolk where when MRJ was three years old the family came through a maternal relative, Jane Anne Broke whom MRJ referred to as "Cousin Jane".5 MRJ used to visit Jane at the seventeenth-century Livermere Hall for tea and he refers to 'roaming' in the park from 'tea at the Hall' in 'A Vignette' (ed. Jones, 401). Trustees of Jane, who was Patron of the living though only twelve years old at the time, had presented it to MRJ's father in 1865 and he remained in post as parish priest for forty-four years (Cox, 43). Herbert had married Mary Emily Horton in Helmingham, Suffolk, and family members were land owners in Suffolk since the sixteenth century (43). As a boy MRJ stayed with his paternal grandparents William and Caroline James, in Wyndham House in Aldeburgh (43). MRJ studied the Abbey at Bury St Edmunds in boyhood, and as an academic wrote about the Abbey.6 MRJ is responsible for the headstones and inscriptions on the monks' graves in the Chapter House within the Abbey ruins (in the public Abbey gardens today).7

Cox comments on the oddness that of all the places known to readers of MRJ's ghost stories, Livermere is probably the least known and yet the most influential upon his life (42). Regarding what Cox refers to as the 'Jamesian image', Cox points out that there is wide awareness of the connections with King's College, Cambridge and Eton, and indeed these were essential and happy influences on M.R. James (42). He wrote of them in his recollections Eton and King's, whilst he wrote little of his formative years in Livermere (42). Yet both Cox and Suffolk Historian Norman Scarfe believe that Livermere Rectory was where MRJ's ghost stories 'took embryonic shape' (Scarfe).8 Michael Cox explains of Livermere, and similarly to Kort's acknowledgement of the dual experiences of landscape:

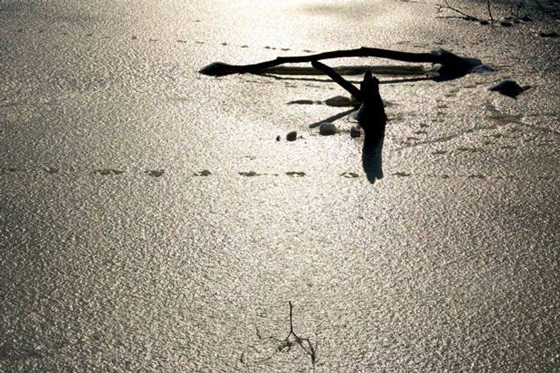

There is beauty and peace here; but also, at certain times and under certain conditions, an undercurrent of menace. From an early age MRJ was alive to these darker resonances of the Suffolk landscapes; in this respect, his childhood at Livermere may be seen as contributing [to] the imaginative foundations of his later fiction. He must also have been aware of the immemorial beliefs still current in an isolated country village like Livermere... (45-46). (Cox points out that MRJ's father disapproved of such beliefs, as does Edward and the Rector, of Lottie in Landsdown!) (46).

Cox argues that Eton and King's on the one hand, and Livermere on the other, 'symbolise the two sides of MRJ's personality'; the scholar and the ghost story writer (46). For where the worlds of Eton and King's provided routine, enclosure and protection, Livermere and parts of Suffolk 'evoke other images' (45). These images are 'more ancient, elemental and unpredictable', and create an 'almost tangible ambivalence – a tension between nature tamed and domesticated (like the conjoined waters of the two lakes)'; yet Livermere endured in MRJ's 'heart and imagination for the rest of his life' (45-46). Of MRJ's childhood in Livermere, Cox says that MRJ's 'natural fascination with the uncanny and the macabre were confirmed and deepened by the ambiguities of the landscape' (46). It is at Livermere, Cox argues, that we 'come close to the secret places of MRJ's inner life' (45). It is here that we perceive 'the sources of that responsiveness to strangeness which lay beneath the reticent, controlled exterior of a man who, whilst deeply conventional in his beliefs... was alive to metaphysical possibilities' (45).

Cox cites one of MRJ's earliest stories 'Lost Hearts' as an example of a sense of place being imbued with 'sinister potential' through the sights and sounds, such as 'strange cries... from across the mere' (Broad Water Lake in Livermere is also called the mere) (46). Cox sees it as 'inevitable' therefore that MRJ would 'return in imagination to Livermere' for his last story 'A Vignette', for the landscape of Suffolk had 'exercised a profound effect on his imaginative life' which resurfaced in his stories (44-46). In this story the reader learns that the narrator is describing a 'spacious garden of a country rectory, adjacent to a park of many acres', and later sees the horrid face peering through the gate, which 'had some formidable power of clinging through many years to my imagination' ('A Vignette' ed. Jones 401-5). Cox says MRJ 'returned to the place that, more than any other had shaped his literary imagination, [for] we are back in the Livermere of his childhood...' (44). Here there is concealment with 'secret nooks and retreats among the bushes', and 'there was a form shambling away among the trees', (405), (see Sylvan Dread).9

M.R. James explained in 1931 that his interest in ghosts was sparked in childhood when he saw a puppet of the 'Ghost' in a Punch and Judy show.10 The youngest of four children, MRJ attended the family daily prayers and bible readings in Livermere Rectory, (Cox, M.R. James, An Informal Portrait, 8). His father was a nineteenth-century evangelical Christian, and a popular preacher and orator; when he was away on church business, MRJ's mother Mary Emily continued the daily devotions (8-9). Although dogma was 'central to Herbert's religious thinking' he and Mary adored and deeply loved their children, wanting each one to be free to prosper according to their own abilities and skills (8-11). MRJ seems from photographs of his childhood for instance, to have enjoyed life, alongside his intuiting the supernatural, and despite being homesick on first leaving home for school (8-11). Although Cox suspects that Herbert was disappointed that unlike MRJ's brother Sydney, MRJ did not become an ordained priest, nonetheless Herbert was especially fond of his youngest son (7).

It is likely that MRJ's literary imagination was influenced by his father's preaching and teaching in the pulpit and home at Livermere; perhaps sometimes of vivid allegory eliciting in the mind pictorial images such as from the biblical books of Daniel and Revelation. According to MRJ's friend Shane Leslie, MRJ had an 'uncanny knowledge of Scripture' which extended to the Apocrypha: '"hidden" Scriptures [such as the Book of Japhet] were the romance of his life'; the word '"apocalypticotatos" might be engraved on his heart [and] tomb'.11 Leslie tells us that MRJ told of a childhood dream in which he 'found himself opening a shiny Folio Bible with an unknown book included with a Hebrew name' (33). He was clearly drawn to the romanticism of undiscovered texts, coupled with his appreciation of the supernatural which 'was stimulated early and never left him', for he was aware of the 'thin fabric that we call 'reality'' (Cox, 6). This thinness can be perceived as parallel to Casey's 'sievelike' edges of places or 'porousness of boundaries' in his theory of place in chapter one (Casey, 39-43). MRJ's religious background either created or heightened those sensibilities in him. This would be all the more so because of the Evangelical concerns with eschatological matters concerning the end of time and judgement. Preaching at Eton in 1933, MRJ explained of his childhood in Livermere:

There was a time in my childhood when I thought some night as I lay in bed I should suddenly be roused by a great sound of a trumpet, and that I should run to the window [and] see the whole sky split across and lit up with glaring flame: [and] I and everybody in the house would be caught up in the air and made to stand with countless other people before a judge seated on a throne with great books open before him: and he would ask me questions out of what was written... then I should be told to take my place either on the right hand or the left (Cox, 9).

MRJ continued to be fascinated by eschatological matters from childhood onwards, along with the lives of the saints (and gruesome details), and stories from classical tales of antiquity, folklore and ghost stories (Cox, 9-10). Cox notes that despite his love of facts MRJ was 'essentially a creature of the imagination' (6). His child-like visionary belief or sense of wonder, first nurtured at Livermere may be aligned with the same vivid imagination with which he created his ghost stories in adult life. Interestingly, MRJ was in some ways considered child-like in his adulthood, his friend A.C. Benson said of him that he had 'the mind of a nice child – he hates and fears all problems, speculation, all originality or novelty of view. His spirit is both timid and unadventurous. He is much abler than I am... yet I feel he is a kind of child', (Jones xiii, Cox, 125). Although Benson's view may have been warped by his depression, modernist Lytton Strachey declared critically of MRJ 'It's odd that the Provost of Eton should still be aged sixteen. A life without a jolt' (Michael Holroyd).12

Darryl Jones has noted MRJ's life was 'an unbroken progress through educational institutions' or, as Suffolk Historian Clive Paine puts it, 'M.R. James never left school' (MRJ died peacefully at Eton), (xii / footnote 6). Jones goes on to observe that without this sheltered life MRJ would probably not have written his ghost stories (xii). According to Jones, the ghost story itself is a 'characteristic product of nineteenth-century forces. It is a reaction to the secular, materialist, industrial modernity that animated the dominant progressivist Victorian utilitarian ideology' (xviii). The reactionary ghost stories espousing a 'thin veil' between matter and spirit were akin to the interests at the time with spiritualism, 'the main Victorian response to secular modernity' [Jones's italics] (Janet Oppenheimer) (xviii). When asked if he believed in ghosts MRJ answered that he was 'prepared to consider evidence'.13 Shane Leslie asked MRJ the question again during his last days, when he replied 'Yes... but we don't know the rules'.14 Leslie felt that MRJ's ghost stories were not a 'side hobby' but 'relief from a secret madness in his inner soul... in spite of all the art and beauty... [and] unfailing friendships... the malevolent and diabolical survived around him in the invisible' (35).

Given this conjecture, possibly King's and Eton afforded MRJ a sense of security or containment which contrasted with the Livermere countryside, with wildness, isolation, strangeness and the place where he seemed to have encountered the unexplainable resistant to order or cataloguing! However, as he informs the reader in Suffolk and Norfolk: 'the rectory [at Livermere] was my home, if not my dwelling place from 1865 – 1909', and that 'The Livermeres [Great and Little, have] beautiful scenery [and] form the most interesting and delightful spots in the county'.15 His parents were buried at Livermere with a large cross which MRJ had erected for them, inscribed with PAX. Probably Livermere represented both happiness and disturbance for MRJ, and perhaps in modern parlance, "You can take the man out of Livermere but you can’t take Livermere out of the man". Livermere, a village of farm and estate workers may have been the antithesis of the jolly erudite milieu of King's and Eton, but it was also the place of an apparently happy childhood and the seedbed of his ghost stories.

Jones points out that the Suffolk landscape of MRJ's childhood informed his stories 'in a profound way' and that Aldeburgh is a 'wild spot... which has attracted artists of a bleak nature' (xi). However Jones argues that more than the East Anglian landscape, it was the 'influence of the educational institutions' and books and knowledge (and fear of them too) which 'dominate' MRJ's stories (xii). Jones tells us that MRJ suffered 'genuine fear of ideas', knowledge and modernism, so much that on admonishing students 'discussing a philosophical problem' MRJ stated "No thinking gentlemen, please", (xii-iii). Jones believes new ideas caused MRJ 'lifelong anxiety' thus he was 'in flight' from them 'all his life' (xv-xvi). This caused him sometimes to clash with modern thinkers or fellow academics, such as John Maynard Keynes (xiv-xvi). Yet as Jones tells us, MRJ's limitations and anxieties account for the 'brilliance of his ghost stories' whereby the threats of modernism are kept at bay (xvii).

Jones attaches the creation of the stories to MRJ's psychology, to being 'a curiously incomplete man' (xii-iii), or as Brian Cowlishaw expresses it 'James wanted to keep the unconscious buried. Freud sought to relieve repression; James to encourage it'.16 Perhaps this repression is a manifestation that MRJ had imbibed proscriptive evangelicalism, his father although intellectually rigorous was probably deeply conservative, and wary of what he called 'ill-regulated speculation', as was MRJ which served him well when applied to scrupulously disciplined academia (xii). However, it could be argued that MRJ's unconscious fears surfaced or were 'exorcised' through his ghost stories. Jones discusses how a contemporary post Freudian reading of MRJ's stories may enlighten us: on MRJ's sexuality, his deepest friendships especially with the McBrydes, fears of knowledge, linen, domesticity and women, and spiders (xxx-xxv).

Both spiders and women feature as threatening entities in 'The Ash Tree', (Jones, ed., 35-47). The narrator opens with informing us of the 'smaller country houses' in Eastern England; then sets the story in one such called 'Castringham Hall' which it is thought was based on the seventeenth-century Livermere Hall (429). It is a 'square block of white' with a 'park with fringe of woods and mere', and a 'great old ash-tree' close to the Hall (35). The nearby district was the scene of 'witch trials' and Castringham Hall's Sir Mathew Fell played his part in the conviction of a witch called Mrs. Mothersole who was hanged (36). The narrator/MRJ makes a comment to the effect of not understanding the vilification of witches (36). Graves in Livermere churchyard engraved with the surname of Mothersole were known to MRJ as was the parish clerk, Mr. Mothersole. Matthew Fell is thought to be a conflation between the Witchfinder General Matthew Hopkins and Sir Matthew Hale (1609-76) MP, a judge in witch trials in Bury St Edmunds, with possible play on the word Fell/fall. Sir Matthew Fell found Mrs Mothersole 'gathering sprigs from the ash-tree' near the Hall and chased her but found only a 'hare running across the park' (36). The ash-tree has inspired associated superstitions and folkloric connections, and the ghost of Mrs. Mothersole now residing in the ash-tree near the Hall, causes her fellow occupants, the very large spiders, to kill Sir Matthew.17 Many years later, his grandson Sir Richard oversaw the building of a 'great family pew' which required graves to be disturbed, including Mrs Mothersole's, though her coffin was mysteriously empty. Various guests staying with Sir Richard when he too is killed include the Bishop of Kilmore (possible play on Kill More) thought to be based on Frederick Augustus Hervey (1730-1803), 4th Earl of Bristol, named the Earl Bishop (with an Irish see), of Ickworth House, a few miles away, and Lady Mary Hervey also of Ickworth house (Clive Paine/footnote 7). The dark sinister overtones of this story are resonant in my imagination whilst walking in the park at Livermere as dusk settles!

In the story 'A Warning to the Curious' there is a beautifully evoked sense of place: Seaburgh a fictionalised Aldeburgh in Suffolk (MRJ in Jones, ed., 419). MRJ describes marshes 'intersected with dykes... recalling Great Expectations', inland 'gorse', a 'long sea-front and a street... a spacious church of flint... and a peal of six bells' (Jones, ed., 343). Of which the narrator, reminiscent of the boyhood of MRJ, tells us 'How well I remember their sound on a hot Sunday in August' (343). MRJ goes on to describe in detail the sense of place poignantly observing that place comes 'crowding to the point of the pencil when it begins to write of Seaburgh' (343). We almost hear that intensity evoked in heaths, gorse, 'a belt of old firs, wind beaten, thick at the top, with the slope that old seaside trees have, seen on the skyline' or running 'towards the... blue sea, white windmills, red cottages, bright green grass, church tower, Martello tower, the soil was very light and sandy' etc. (343). We learn that the narrator is staying at The Bear, which is based on The White Lion Hotel, overlooking the sea, and that one of three holy Saxon crowns has been found (344, Jones ed., 460). Nearby historically significant Sutton Hoo, Rendlesham and Dunwich are evoked (344, 346-8/460). When things turn sinister in the story, the same details describing the landscape so beautifully at the beginning create an altogether darker atmosphere (353).

Atmosphere is part of setting, as MRJ said of place in ghost stories; there are 'two ingredients most valuable... the atmosphere and the nicely managed crescendo'.18 He also stated that having read many ghost stories he concluded that 'the greatest successes have been scored by authors who can make us envisage a definite time and place'.19 For as MRJ explained, 'Setting or environment, then, is to me a principle point, and the more readily acceptable the setting is to the ordinary reader the better' a ghost story is enjoyed.20

I think one writer who has succeeded with her evocations of a sense of place in a ghost story is Susan Hill, an admirer of MRJ.21 For instance in Hill's bleak East Anglian landscape in The Woman in Black, and, I think much more beautifully, in The Small Hand.22 A haunted house and garden, a monastery in France and Suffolk, all feature in this short novel. Her protagonist is a dealer in antiquarian books and manuscripts, and using pared down prose she describes place and atmosphere: the run-down 'solid Edwardian house... obscured by rose briars' which had been 'left to the... wind, sun, the rabbits, left to fall gently, sadly into decay, for stones to crack, windowpanes to let in the rain and birds to nest in the roof' (13). We are told 'it would gradually sink in on itself and then into the earth' (13). The garden is 'covered' with 'blankets of ivy and trailing strands of creeper, thickened over with weed', sucking the 'light and air out of it' (13). The place is reminiscent of Great Expectations (which is referenced in the story), and needless to say is the site of a tragedy; a young boy, drowned in the garden pond, whose ghost seeks revenge, appears in different places including at the Cistercian monastery of Saint Mathieu Etoiles (where the dealer seeks a first folio kept in their library). Hill describes the importance of a sense of place; 'what the ghost story [depends] upon more than anything [is] the atmosphere and a sense of place... the plot is not the most important thing'.23

Hill's haunted house and garden, MRJ's haunted grand houses, libraries, etc. as hopefully with my own Landsdown Hall, all act as haunted sites or 'key figure(s) for history-as-suffering', 'instantiated' in 'feudal property as aristocratic mansions'; acting as loci of trauma where history bursts into the present.24 Hay says of MRJ that his 'naturalistic' style is evidenced in his 'precise and loving attention to detail' including of place (99). In MRJ's bourgeois places, grand houses, archives and libraries for instance, history is in need of resistance to being called forth from the dead or the past. It can be protected by 'marginalised knowledge of scholars, archivists and antiquarians' (101). Yet despite place being problematic, MRJ's stories offer unusually satisfying endings which Hay argues is a retreat from the social realist project – in keeping with MRJ's fear of ideas and modernity. However Jones points out that modernity 'is terrifying [and] demonic' [Jones's italics], something MRJ witnessed at King's and wider with the great losses or injuries of men during the Great War (Hay 98/Jones, ed., xxix).

Therefore Jones states that MRJ's stories articulate 'a particularly English longing for the past' as a reaction to the terror of the modern, and Hay theorises that MRJ's 'bourgeois' stories highlight 'the past and its inheritance by the present' (xxix, 93). MRJ's characters are often 'antiquarians, academics, librarians, archivists... clerics and curators'; they 'know about old things' but their methodologies of knowing are 'outmoded, persisting into a modern world' where such is 'increasingly marginalised' (Hay, 96). They 'are odd heroes, fusty and fussy, with some sense of the dust of the library or the chapel lingering on them' (96). Messing 'around in the archives' disturbs 'records of the past [and] prompts the ghosts to turn up' or 'bumbling modernizers' cause this which 'antiquarians then lay to rest' (96).

MRJ's characters are 'acted upon' by place or settings which are 'lovingly' specified with Hay citing the opening narration to 'The Ash Tree' as a good example (94). However, MRJ's stories alert us to the 'bourgeois desire to inhabit the physical and social' places of 'the old gentry' as being 'dangerous, inviting that past to play a deadly role in the present' (95). Hay points out that we are also taken into interior places; 'inside the heads and hearts of characters' (104, 107). Individuals and their felt experiences in specific places are primary to MRJ, rather than society politic. Hay argues MRJ's stories are therefore a 'distraction' from social reality, preferring concerns about aristocracy and aspirations (123). Hay argues that a ghost is 'the residue of some traumatic event that has not been dealt with, [and] to be concerned with ghost stories is to be concerned with suffering... historical catastrophe [and] mourning', for they are a 'mode of narrating what has been unnarratable' (4).

Simon Hay examines ghost stories in relation to history, trauma, class and property; like Casey, he argues that 'history resides in architecture and landscape; time and memory take on embodiment' (14). The folklorists Goldstein, Grider and Banks Thomas, believe that history, time and memory are embodied in place - landscape and architecture, and that ghost stories play a pivotal part in reinforcing the connections to place. Ryden, from the point of view of a folklore scholar, makes similar points about stories per se and place. Banks Thomas notes that ghost stories draw our attention to place; to 'aspects of the world..., the supernatural can be used to contemplate nature and place' (44).25 She suggests asking what ghost stories reveal about landscapes, the reader and author's response. This could be applied to MRJ's formative encounters in the Suffolk landscape informing his stories. Banks Thomas experienced transformation of her feelings or 'attitude towards place' due to the ghost stories located there (45). She was reminded of the 'mystery and power' of place, and supernatural narratives create 'bonds to place... because they deal with the metaphysical... a larger place' (45). These thoughts resonate with my own experience when roaming the park at Livermere.

Sense of place in ghost stories is often distilled into haunted houses (like MRJ's, Hill's, Landsdown Hall, etc). Similarly to Kort's theory of house/home attachment and intimacy, Grider tells us that humans are powerfully attached to houses as 'sanctuaries' (143). However, ghosts disrupt our sense of safety normally attached with houses, which once haunted, are an 'evil mirror of the enchanted castle' (143, 149). Ghosts change 'an otherwise mundane place into a portal through which the living encounter... the supernatural' (143). Doors, staircases etc act as thresholds between 'reality' and the supernatural, much as the gate does in 'A Vignette', as I hope it will in Landsdown (170).

In contrast to a historic or folkloric approach to ghosts, Mayerfeld Bell examines ghosts from a sociological viewpoint, arguing that ghosts are 'social constructs' and we experience them 'socially as we do people' (814, 821).26 They are a 'ubiquitous aspect of the phenomenology of place', the felt presences in our memories of the dead and living (the absent or our own younger selves, such as Toby recalls his boyhood self in Landsdown), (831-2). Ghosts affirm the 'historicity of historical sites', for 'places are personal – even when no-one is there' (814). Sociologists recognise human need to imbue place with presence and meaning, which gives ghosts 'good reasons to haunt specific places... mediated by the landscape' (819, 821, 831). We need ghosts for 'real consequences for social life' and for the 'world to remain an enchanted place' (831-2). Mayerfeld Bell posits that we create 'ghosts of place' via our 'own imaginations' and consequently they are our ghosts, personal to us. Only people can 'conjure' their own ghosts; it is only we who 'give ghosts to places' (831). Sensing ghosts in 'a place' can ensure we 'experience a deep sense of belonging to' or even 'special possession' of that place' (824). It seems that MRJ felt a sense of 'belonging' to Livermere, a place which helped to form him as a ghost-story writer.

Conclusion

Suffolk and ghost-stories resonate with me personally, for as a child growing up in a village a few miles from Livermere, I often visited the village poacher who told me of his frightening encounter with a ghost in the woods one night. It followed him through the dark woods until he could at last slip away from the spectre. Sitting by his sweet-smelling crackling wood-fire I watched shadows flickering across his wizened face and his milky-blue eyes widen as a look of terror froze into his old face. We sat quietly for some time in the mystery of his strange encounter. Of course as an adult I have wondered if his guilt at poaching had created the experience! But as a child, on saying goodnight to the poacher, and leaving him with his pheasant supper, I certainly wondered if it were footsteps I heard following me as I ran as fast as I could all the way home that evening - without once looking back!

In writing Landsdown and exploring place and MRJ, I have reflected on the importance of a sense of place. Seamus Heaney claims there are 'two ways of knowing place; 'one is lived, illiterate... unconscious, the other is learned, literate [and] conscious'.27 I hope I may have employed both ways in my explorations in this dissertation. In the writing process I have discovered that a sense of place has influenced how I imagine a story and its characters, and how places have influenced and formed me as a person, and as a writer I hope.

In my view, Casey's enquiry into the perception of place as primary is exciting. Bachelard's deeply layered exploration into the intimacy of place is especially pertinent to creativity. Kort and James seem to me to be justified in their appeal for literary criticism to more prominently evaluate a sense of place in fiction. Ryden's thesis on the inextricably bound or symbiotic relationship between place and stories makes sense of the deep meanings of place.

M.R. James remains an endlessly fascinating man and writer of wonderful ghost-stories. Jones, Cox and Joshi and Pardoe have all enlightened me on MRJ and Great Livermere. I am also grateful for the insights of Hay, Goldstein, Grider, Banks Thomas, and Mayerfeld Bell, and I am grateful to M.R. James himself. All of these writers have contributed to my understanding of the creative process of envisioning and writing a fictionalised and haunted place in Light over Landsdown.

Notes

1 From a poem about Livermere written by M.R. James, aged twenty-six, and sent home to his sister from Cyprus.

2 There have been three Halls at Livermere. The site of the former medieval Hall is in the park close to today's Hall, as is the seventeenth-century Hall which was demolished in 1923. This was further into the park on the slight hill (and on the left when facing Ampton), overlooking Little Livermere Church and Broad Water Lake. The current Hall is the former Georgian Rectory now called Livermere Hall, often used for shooting parties.

3 'A Vignette' in M.R. James Collected Ghost Stories, Edited with an Introduction and Notes by Darryl Jones, (Oxford University Press, 2011), 401 – 405, 466. Subsequent page references in text.

4 Michael Cox, M.R. James, An Informal Portrait, (Oxford University Press, 1983), 'Note' before chapter one. Subsequent page references in text.

5 Michael Cox, 'M.R. James and Livermere', in Warnings to the Curious – A Sheaf of Criticism on M.R. James, ed. S.T. Joshi and Rosemary Pardoe, (Hippocampus Press, 2007), 42-43. Subsequent page references in text.

6 M.R. James, On the Abbey of Saint Edmund at Bury: I. The Library II. The church. (Cambridge Antiquarian Society. Octavio. Publishers. No. xxviii, 1895). See also Cox, pages 15, 117.

7 Clive Paine, Suffolk Historian, Lecture on M.R. James and his tales of the imagination, Suffolk Records Office, Bury St Edmunds, March 2012. (Clive is writing a book on East Anglian writers including MRJ).

8 Norman Scarfe, 'The Strangeness present: M.R. James's Suffolk', in Warnings to the Curious – A Sheaf of Criticism on M.R. James, ed. S.T. Joshi and Rosemary Pardoe, (Hippocampus Press, 2007), 40. Subsequent page references in text.

9 Steve Duffy, '"They've got Him! In the Trees!" M.R. James and Sylvan Dread', in Warnings to the Curious, A Sheaf of Criticism on M.R. James, (Hippocampus, 2007), 177-196.

10 M.R. James, 'Ghosts – Treat Them Gently!' Evening News (17th April 1931), in M.R. James Collected Ghost Stories, ed. Darryl Jones, (Oxford University Press, 2011), 416. Subsequent page references in text.

11 Shane Leslie, 'Montague Rhodes James' in Warnings to the Curious, A Sheaf of Criticism on M.R. James, ed. S.T. Joshi and Rosemary Pardoe, (Hippocampus Press, 2007), 33. Subsequent page references in text.

12 Darryl Jones, Introduction, Collected Ghost Stories, (Oxford University Press, 2011), xiii, xii, xiv. Subsequent page references in text.

13 M.R. James, Preface to The Collected Ghost Stories of M.R. James (1931), Ibid, 419.

14 Shane Leslie, 'Montague Rhodes James' in Warnings to the Curious, A Sheaf of Criticism on M.R. James, S.T. Joshi and Rosemary Pardoe (ed.), (Hippocampus Press, 2007), 34, 28-37. Subsequent page references in text.

15 M.R. James, Suffolk and Norfolk, (J.M. Dent and Sons, 1930), 71.

16 Brian Cowlishaw, '"A Warning to the Curious": Victorian Science and the Awful Unconscious in M.R. James's Ghost Stories', in Warnings to the Curious, A Sheaf of Criticism on M.R. James, S.T. Joshi and Rosemary Pardoe, (Hippocampus Press, 2007), 163. Subsequent page references in text.

17 Rosemary Pardoe, '"A Wonderful Book": George MacDonald and "The Ash Tree"', Ibid, 242-247. Subsequent page references in text.

18 M.R. James, 'From the Introduction to V.H. Collins (ed.), Ghosts and Marvels', (Oxford, 1924), in Darryl Jones, M.R. James, Collected Ghost Stories, (Oxford University Press, 2011), 407.

19 M.R. James, 'Some Remarks on Ghost Stories', The Bookman, (December 1929), 169-72, Ibid, 415.

20 M.R. James, 'Ghosts – Treat Them Gently!', Evening News (17th April 1931), Ibid, 417.

21 Susan Hill, Introduction, The Woman in Black, (Longman, 1989), viii.

22 Susan Hill, The Woman in Black, (Longman, 1989), and The Small Hand, (Profile Books Ltd), 2010. Subsequent page references in text.

23 Susan Hill, Introduction, The Woman in Black, (Longman, 1989), vii. Subsequent page references in text.

24 Simon Hay, A History of the Modern British Ghost Story, (Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), 12-3. Subsequent page references in text.

25 Diane E. Goldstein, Sylvia Ann Grider and Jeannie Banks Thomas, Haunting Experiences: Ghosts in Contemporary Folklore, (Utah State University Press, 2007). Subsequent page references in text.

26 Michael Mayerfeld Bell, 'The Ghosts of Place', Theory and Society, Vol.26, No. 6 (Dec. 1997), 813-836. (istor.org). Subsequent page references in text.

27 From a blog article about Seamus Heaney's 'The Sense of Place' and 'place-consciousness in the Irish literary imagination', Heaney's "Broagh": The Word made World, the article's first appearance was in The Boston Irish Reporter, Volume 17, Number 5 (May 2006), p.25. http://www.irishmatters.blogspot.co.uk/2008/10/heaneys-broagh-world-made-word.htm.

About the article

Through a Gate Darkly

'Through A Gate Darkly' formed part of the Critical Commentary of an MA dissertation I wrote in 2012, in which I explore a sense of place. This chapter examines how Great Livermere in Suffolk, family home of the great ghost story writer M.R. James, may have influenced him and his stories.

The images of Great Livermere were produced by Caroline Fitton, photographer and writer.

About the author

Julie Eaton

I have worked in Suffolk, Norfolk, Essex and London, though Suffolk is home. Following a Literature degree I enjoyed the Masters in creative writing course at the University of Essex and through the module Memory Maps became intrigued by a sense of place and stories.