The Great Tide

Jules Pretty

Excerpt from Jules Pretty, This Luminous Coast, Saxmundham: Full Circle (2010)

This is a coast about to be lost. Not yet, but it will happen soon.

Every East Anglian of a certain age still remembers the 1953 floods, where the sea walls were breached in over 1000 places, as with no warning whatsoever wild gales brought roaring waters down the North Sea and crashed them over land into houses. Such extreme events were thought to be rare, but perhaps we need to ready ourselves. On 9 November in 2007, spring tides, north-easterlies and low pressure combined to raise the sea to levels that in places surpassed those reached that terrifying January night 54 years earlier. The sea almost broke through at Walcott in Norfolk, and on long stretches of the coast today's higher sea walls came within a few centimetres of being overtopped.

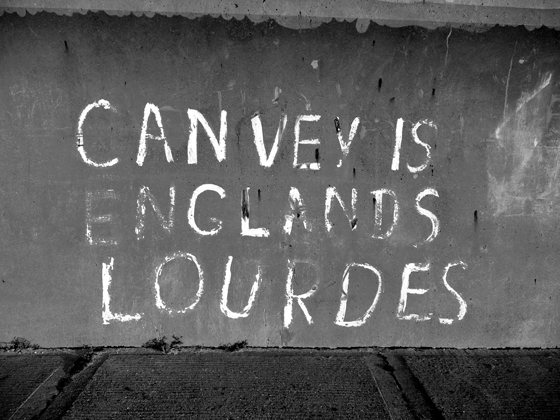

A few days after this tide, I came to be walking around Canvey. On this Sunday morning, I cross the marshes towards the flaming oil refinery, past kids playing football on parks besieged by gasometers, clusters of wrapped parents shouting from the half-way line. Inside the walls, people and homes are alongside industry and now faded tourist glory. Outside are beaches, creeks, saltings and the estuary. I set off from the famed Lobster Smack Inn, a reference point in Great Expectations, dwarfed by a concrete sea wall with its walkway now level with the pub's upper storey. A century ago, on his Marsh Country Rambles, Herbert Tompkins stopped here to watch the boats from the pub. "The weather did not invite merriment," he wrote. "We put our backs to the wall and our legs under the heavy table; watched the flicker of the fire upon oaken beams, exchanged a few anecdotes, and smoked our pipes in peace." What more might any traveller want? Today, a nor'westerly gusting to gale force brings the rain horizontally along Hole Haven, and I have to bend into the wind to stay upright.

I walk down the jetty by the old customs watchtower, carefully over the mud-slick wood, and turn to look back at the sea wall. All around the 15 mile perimeter of the island are 5-metre concrete walls, holding in the houses, keeping out the water. Later as I walk along the inside of the wall, I will see deposits of bladderwrack and smashed portions of squid and other sealife, brought over by those recent massive tides. When you look inland from this castle wall, though, and imagine the weight of water when the sea is full, then you sense just how tenuous is life below sea level, even here in what seems like a mostly benign estuary.

Like many major natural disasters that remain fixed in personal and national psyches, nobody saw the 1953 floods coming. Even as that Saturday night unravelled, still no one could imagine the sea coming in with such devastation. It all began when a low-pressure zone deepened over the north of Scotland on Friday 30 January, producing sou'westerly winds over in the North Sea, and driving water from south to north. In the early hours of the Saturday, just one tide away from disaster, the high tide was a foot lower than it should have been at Southend. Then as the depression travelled rapidly east, the winds veered to northerly, and water from the Atlantic was suddenly driven back into the narrow North Sea. By six o'clock, air pressure had dropped to 968 mb over the Orkneys, bringing the sea level up by an extra foot. Still weather forecasters were predicting no more than a "vigorous trough of low pressure". But the pressure over the North Sea would lock between 968–976 mb until midnight on the Saturday, by which time so much water had piled up in the North Sea that the defences on the east coast would at first be threatened, and then in a short few hours overtopped, breached and then soundly beaten.

The problem was not the occasionally very strong gusts, but the extraordinarily high average wind speeds maintained over many hours. These prolonged and violent winds forced an extra 15 billion cubic feet of water into the North Sea, raising sea levels by an extra 2 feet. The tide came as a giant standing wave, hundreds of miles long, arriving at King's Lynn five hours before Harwich, and seven hours before Tilbury on the Thames. This night's tide would be higher than ever previously known. Now two key factors were in place – very low pressure and strong nor'westerly winds. The third was the full moon on the Sunday. Full and new moons bring spring tides, when high tides are highest. As people in coastal communities in Lincolnshire, Norfolk, Suffolk and Essex went to bed that Saturday night, none knew of the coincidence of these three circumstances. None had forward warning of the risk. No one would be able to do anything but try to save themselves and their families as the tide came in, and in.

Signs of unusual sea levels were noticed that Saturday afternoon, when no ebb occurred. The wind "seemed to be holding the water", reported one policeman. Across the North Sea, where the loss of life was to be far worse in the Netherlands, no ebb was recorded either. That night, the high tide should have been 5.5 to 9.6 feet above Ordnance Datum Newlyn from the top to bottom of Essex. It was to be 13.1 feet at Harwich, 14.4 feet at St Peter's, 15.9 feet at Tilbury, and 16.9 feet at Barking, the highest on record. By five o'clock, as football supporters from across the region were trudging home for tea, sea water crashed through the dunes and sea walls in Lincolnshire, and local crises were unfolding. Every automatic tide gauge in the Wash, and eventually all those to Southend, would be destroyed by the enormous weight of water. But still the worries and actions were localised. Then the 7.27 evening train from Hunstanton to King's Lynn ran headlong into a wall of water a mile inland from the north-west Norfolk coast, and was to be stranded for six hours. And now the first serious disaster occurred. Forty bungalows on an estate in south Hunstanton, home mainly to American servicemen and their Norfolk wives, were flooded, and all but three collapsed and were swept away. Sixty-five people drowned.

At Sea Palling, 6 metre waves burst through a 100-yard gap in the sand dunes, and rushed inland. Yarmouth was engulfed at ten o'clock, still three hours before their high tide. At sunset in Harwich, it was difficult to stand in the wind, and heavy seas were crashing deep into the harbour and Stour and Orwell Estuaries. Anxiety increased, and local fishermen and yachtsmen shared their worries about the poor ebb and severe winds. Yet down at Tilbury, a lookout near the fort recorded only that the "wind was fresh, but the water calm as a mill pond". In the previous eight winters 56 warnings had been received from the Met Office about high tides associated with north-westerly winds, but none were this high. It is difficult today to imagine the lack of real-time information. No regular updates of news; no mobile phones; no internet; landlines linked only via local exchanges constrained by the need for human operators; few families with phones at all. No one in Essex knew of the Hunstanton train-stranding and drowning disaster. Today, this is inconceivable.

By ten o'clock in the evening, all down the Essex coast the sea had completely covered the saltings, and was working away at the sea walls themselves, filling rabbit burrows and badger setts, loosening cracks in the clay, undermining foundations. At Maldon, a group of fishermen decided to sleep on their boats to keep a close eye, and half an hour later all the rest had gathered on the quay quite unable to get out to their boats. One out on the water recorded gleefully, "You should have seen 'em, there they were standin' up on the benches along the prom, squawkin' and hollerin' like a lot of old crows." They did, though, spend the night looking after their rivals' boats on the Blackwater. The drama was mounting at every location, ready to play out in the bitter wind and fearsome conditions. At the time no one knew where the sea would stop. Now the events of the last day of January and the first few of February were to unravel almost minute by minute.

In Harwich, the water tops the quay and starts to spill into the streets. A police constable hurries from house to house from eleven o'clock, knocking on doors, and then finds himself pursued down the street by rushing waves. By half past eleven, the sea is pouring into the town, and a 3 foot wall of water is crashing into houses and seething up roads, almost stealthily beneath the roaring gale. A fisherman on Alemeda Road is warning neighbours on his still-dry street, comes home to gather up his wife and children, but then a wave crashes through their small house. He manages to carry them one by one to higher ground. Elsewhere, families stand at the top of their stairs, shaking after explosions of water smash through windows and doors below. They wonder where the rising water will stop. Looking out, they see waves crashing into fences and pounding houses, and pigs being washed along by the current, and do not know what they will do if the water comes into the bedrooms.

Further south at Walton, just like on Southwold, Fobbing and Tilbury Marshes, the sea water sneaks in the back door and whilst everyone is looking seawards to the waves and the wind, it drowns houses from the land side. At Jaywick and Canvey, people are sleeping behind 1,000 year-old sea walls, trusting to history, but will be betrayed. The walled fortress of Essex is under siege, and soon will surrender.

By the Blackwater at Canney Farm, a farmer watches the rising river. After the final milking of his magnificent dairy herd of 17 prize-winning Friesians at 11.30, he comes out of the shed and in the bright moonlight (by now, the ghostly moon is beginning to light Essex, but the wind is not letting up), he looks across a white landscape. Like others from Foulness to Felixstowe, he thinks at first it is snow. But then he realises his mistake, and sees the tide rushing across the fields towards the barn. He is reluctant to turn out the cows for fear of them catching pneumonia, a fatal decision. He runs to a neighbour's to find out the time of the high tide, but when they both return, the fields are all waves, crashing onto the cowshed, some lashing right over the roof. This is not just water, it is the full-blown sea, with waves and currents and now 4 to 5 feet deep. They try to get the herd to move, but the animals fear the water too much. One by one, through the night, the cows lose feeling in their legs, and pitch into the water. The old bull, though, eventually stands for 36 hours in the freezing water, and survives. All the rest of the famed herd is lost.

The first person to notice a problem on Canvey itself is Derek's father, a River Board man who built his own house when moving to the island, and who that night goes up onto the walls overlooking Tewkes Creek just before midnight. In the hard silver moonlight, he sees a fleet of water where there should be islands across to mainland Leigh, and the sea is lapping over the wall at his feet. He rushes to wake his wife and son, and with another Board man begins knocking up as many people as possible. "The tide is in," they shout. The walls here are a foot and a half lower than on the south side of the island, and this is soon to consign these northern neighbourhoods to 6 to 8 feet of bitterly cold sea water. Derek himself wakes his grandmother next door, who only has a single-storey chalet, and they come back to the bungalow, just a few metres from the sea wall. They retreat to the loft, and so far, apart from the howling wind, not a lot seems to be happening. Mother decides it's time for a cup of tea, a perfectly reasonable request in the circumstances, and Derek is standing by the gas hob downstairs watching the kettle when he hears the sound of trickling water. He turns, and sees water jetting through the key hole halfway up the back door.

Bang. The door crashes open, and the bitterly cold North Sea is inside. He scrambles across the kitchen, fighting the swirling water, and just makes it to the stairs before the house fills to the picture rail. They are trapped. It is the speed that is shocking. With the wind roaring, and icy sea inside the house, the electricity off, and nothing to drink, life seems to hang by a thread. Outside, Derek's father is down the road when the waves overtake him, and he leaps onto an iron fence and grabs a tall post, and there he stays, up to his chest in winter water all the night. Across the road, an elderly couple he has warned climb onto a wardrobe in their tiny bedroom, but later it gives way in the pitch dark, and the woman tumbles into the water and drowns. Like so many others, the husband is quite helpless, even though he is so close. All the clocks in Sunken Marsh stopped between 1.42 and 1.47 a.m. as the rising water reached past the mantelpieces.

In our walled-in fortresses of East Anglia, 1,000 years of protection count for little when finally nature takes the upper hand. Then there are but seconds and inches between terror and survival, and terror and death. Our coast is sinking, our sea is set to rise by three-quarters of a metre this century, could be less, could be more. We sit here, hoping for deliverance. We now know so much more about what climate change could bring, and yet appear to be doing far too little. Since 1953, Derek has watched from the same home as the walls have been raised, and defences strengthened. Will this be enough for the challenges likely to follow?

In all, more than 230 yards of sea wall around Sunken Marsh were breached and scoured to ground level that night, and the neighbourhood came to be described as a basin of death. Many houses had outside stairs, so that residents could live in the loft in the summer, and rent the main rooms to holidaymakers. But as the water gushed in, people had to get outside in 3 to 4 feet of water, and try to climb to safety. For one 70-year-old man, "The pressure of water was so great that the lock wouldn't turn. I had to break it off with a hammer. I shall never forget the shock as the door flew open and the icy cold water poured in with overwhelming force."

It was in that second hour after midnight that the horror in Canvey's Sunken Marsh was worst. Hilda Grieve says, "The cool gallantry of one must speak for all," as she tells this story. One young woman with husband, two girls of 11 and 5, and a baby of 8 months, live in a bungalow beside the central wall. She wakes to the sound of rushing water, and sees the baby's cot floating by her bed. They jump up and force the front door closed against the water, and the husband, who cannot see well as his glasses are lost, holds up the baby, and then climbs out onto a windowsill. The youngest girl perches on the sewing-machine table, whilst the other stands with water up to her shoulders. The mother then sets off to try to swim the 30 metres to the central wall for help. Halfway, she realises the current is too strong and the water too cold, and returns to climb the outside stairs to the loft. She tears blankets and bedding into strips to make a rope, and leans out over her husband 8 feet below. First she pulls up the baby, then the 5-year-old, who is almost too afraid to have the makeshift rope around her armpits. Then the heavier older girl is pulled up and pushed from below, and finally the husband grasps his wife's hands and hauls himself up to safety.

But some tragedies are almost too painful to bear, even after all these years. A few hundred metres away lives a family with nine children under 16 years of age. When the water bursts in, Father climbs on a table to break a hole in the ceiling, and lifts seven of the children one by one into the roof space. Then the table collapses, and Mother is left standing in the water, holding onto the two youngest boys. During the endless, bitter and dark night, both die in her arms. There is nothing she can do. At eight o'clock in the morning, a third small boy falls through the ceiling, and an elder brother jumps in and stands in the 5 feet of water holding him up. Eventually, his legs go numb, and he has to let the small one go and drown. He hangs onto a door until the first boat eventually arrives. No accounts do justice to the lonely despair, the shouting and urging, and the clawing sense of failure as those smallest children died. All survivors will remember this night for all their lives.

In all, 58 people lost their lives on Canvey, 30 from Sunken Marsh alone. In the whole of the Second World War, 81,000 men, women and children were made homeless in Essex by enemy air attack. These floods made 21,000 homeless in one night. Many remember the millions of earthworms, drifting and swaying in the water, killed by the salt. But one famous image is of a group in a rowing boat on one of the main streets. Around the neck of a stuffed bear hangs a daubed sign saying Bear Up. Canvey will live again. On Canvey, the rescued people walked off the island, and some were then taken by bus to local schools and church halls. Canvey was then closed to prevent looting. Large S's were chalked on doors after houses and shops had been searched. The RAF brought on mobile blowers to dry houses, and replacement earthworms were imported from the mainland. "The sea's triumph," wrote Hilda Grieve, "had been stunning."

Yet soon after, the people of the three counties were fighting back vigorously. And this is the untold part of the 1953 flood story – the rapid mustering all along the coast in response to this surprise attack. Voluntary organisations and services were called out: the British Legion, Territorial Army, churches, Women's Voluntary Service, Red Cross, Salvation Army, scouts and guides, YMCA, police, river boards, MPs, councils, schools, fire brigades, Army, Air Force, ambulance service, doctors, fishermen and oystermen. But as all these people were engaging in the rescue, they also had to anticipate the next high tide on the Sunday afternoon. Later, the perspective shifted when all 1,200 breaches along the whole coast, of which 839 were in Essex, had to be repaired before the next spring tides two weeks later. This was to be an extraordinary effort which, save for a couple of locations, would be successful in blocking out the sea again.

This race against time centred on getting huge numbers of sandbags to the holes in the walls. At the time of the flood, the Essex River Board had only 54,000 in stock. A 100-yard breach 5 feet high and 4 feet wide, though, requires 40,000 sandbags to fill it. The river board asked for a million bags a day. At Colchester, 1,000 volunteers went to the pits at Shrub End, Rowhedge and Ardleigh to fill 90,000 sandbags in a day. By the next weekend, 8,000 civilians and servicemen were working on the sea walls, and over the next fortnight 8 million sandbags would be filled and laid. In due course, 2 to 3 feet were added to the sea walls.

The sea was repelled, and the walls along the whole of the coast raised, strengthened with concrete, and raised again. For 50 years, they did their job. Climate change will raise sea levels, and there suddenly emerges a belief that it will cost too much to protect all the coast. Some fields will go into managed retreat, and helpfully produce new saltings. But national and local government agencies decide to save money by letting some defences go unrepaired. No one who experienced the great tide or its aftermath quite believes how much has been forgotten.

About the article

The Gread Tide

'The Great Tide' is an excerpt from This Luminous Coast, a social and ecological portrait of one of the richest and yet least-known regions of Britain, pubished by Full Circle in 2010.

Over the course of a year, Jules Pretty walked the coasts of Essex, Suffolk and Norfolk, completing some 400 miles on foot, and travelling another 100 miles in various boats. This is a coast about to be lost. Not yet, but it will happen soon.

A thousand years ago, a king commanded the waves to retreat to show human futility in the face of nature. Others built seawalls and estuary defences. Small stretches of cliffs provided natural protection, as did shingle heaped into banks. Revetments were added, and sea walls raised, yet still churches, houses and whole settlements fell into the sea. The common field system prospered and went, then the agricultural revolution, and lately came the industrial age. We humans thought we were in control, but now some predictions are gloomy.

In 50 to 100 years, perhaps no landscapes by the sea will survive quite as they are today. What, some may ask, is there to lose? This Luminous Coast a narration of the land and the sea, their wild places and intertwined social history, their places of deep significance to both local people and visitors. Throughout the book are the region’s vast skies, stretched lands of golden cereal, dusty combine harvesters, sea walls of dried grass, thistledown and golden samphire, and white sails gliding across the land on invisible creeks. One some days, there was the hammering of hail on a river wall, drenching rain in a pine forest, crisp hoar-frost on grass at winter’s dawn. Overhead were curlew and redshank and the outpourings of skylarks.

The book is illustrated with the author’s black and white photographs, and has been described as “the best of English topographical writing, combined with an acute ear for the local and the particular” (Ken Worpole). This Luminous Coast was East Anglian nature book of the year (Nov 2011), and short-listed for The Writers Guild non-fiction book of the year (Nov 2011).

About the author

Professor Jules Pretty OBE

Jules Pretty is Deputy Vice-Chancellor at the University of Essex, and Professor of Environment and Society. His 18 books include This Luminous Coast (2011), Nature and Culture (2010), The Earth Only Endures (2007), and Agri-Culture (2002). He is a Fellow of the Society of Biology and the Royal Society of Arts, former Deputy-Chair of the government’s Advisory Committee on Releases to the Environment, and has served on advisory committees for a number of government departments. He was a member of the Royal Society working group that published Reaping the Benefits (2009) and was a member of the UK government Foresight project on Global Food and Farming Futures (2011). He received an OBE in 2006 for services to sustainable agriculture, and an honorary degree from Ohio State University in 2009.

Links

Professor Jules Pretty OBE

www.julespretty.com - Jules Pretty's personal website

Jules Pretty's profile - School of Biological Sciences at the University of Essex