Relics of John Clare

James Canton

Beautiful woman, visions dwell

Of heaven’s joy about thee,

And every step I take is hell

That walks thro’ life without thee.

Sweeter than roses was the face

For whom I pluck’d the flower;

Sweeter than heaven was the place

In that delightful hour.

John Clare, Untitled [1841?]1

It is an enticing tale. John Clare, the 'Peasant Poet', born of the flat fenlands of Northamptonshire, is holed up in the hills north of London. Once acclaimed for his pleasant, pastoral verses by the city cognoscenti, Clare is now out of favour. Fear and worry for the welfare of his wife and seven children unhinges his mind. He finds himself an inmate in the forests of Essex. In the spring of 1841, Clare, who has already spent three years in the asylums of Dr Matthew Allen at High Beach, Epping Forest, wanders the pathways of the forest. He has started to write poetry once more, his mind calmer in the peace of the Essex woodlands. On one of his walks Clare meets a young English painter who has also found inspiration amongst the beeches and hornbeams. Juan Buckingham Wandesforde is learning his trade by sketching the landscape. In the splintered sunlight, the two work: Wandesforde stands at an easel, playing with colours to find those resonant of the dappled shade, the beech leaves, the knurled sinews of the hornbeam trunks; Clare scribbles lines, forging from the forest a return to verse.

Clare's manuscripts show how he would write on whatever scraps of paper came to hand and the poet entrusted his new friend with various odd snippets of stanzas, lines drafted in favoured hideouts amidst the woods. The fragments of verse above are just two examples. The unknown painter whom Clare befriended became a repository for the poet's odds and ends. But Wandesforde was keen to travel, to see the world. When he finally settled in California in 1860 he still had those fragments he had received from a gentle figure of Epping Forest. Some years after Clare died in 1864, Wandesforde released the jottings to be published in a San Franciscan journal titled The Overland Monthly in February 1873. Clare's pencilled flotsam had travelled thousands of miles. Thirty-two years had passed since they were first scribbled. The commentary accompanying their publication noted:

Some of these are now partly illegible, and some are quite fragmentary; but two or three are perfect, and, our readers will admit, quite beautiful, despite apparent defects, which the revision we do not feel at liberty to make would remove.2

Yet there was a further twist to the tale. All but one of these far-flung relics of Clare turned to ashes in a fire that destroyed Wandesforde's home in Hayward, California. That lone remnant somehow wound its way across America. It now rests in the archive of the Massachusetts Historical Society in Boston.

∗

I headed to High Beach on a warm day in April. The tale of Wandesforde and those fragments of verse which had journeyed from Essex to California caught my imagination. I wanted to explore the memory of Clare's time on Essex soils. I wanted to walk the paths Clare had walked and to sit where he had sat and in so doing get a sense of the great rural poet and his craft, perhaps even his madness. It was a romantic notion and one incongruous with the experience of the M25 whose concrete avenue shuttled me to within a couple of miles of the site of Clare's old Essex home. I intended to find that place behind St Paul's chapel where Clare had preferred to sit and compose his lines. There I too would sit, and strive to conjure up his spirit amidst the trees. Then, I would walk away from High Beach and the asylums, following the same path that John Clare trod as he left Essex in July 1841. It was a simple plan, except for the fact that the chapel had been demolished back in 1885 and the route Clare took to Enfield on the start of his epic journey home had never been properly retraced.

At the Suntrap Field Centre, I asked an understandably suspicious gardener if he could guide me to the person in charge. The field centre was on the site of Fair Mead House, the centrepiece of Matthew Allen's asylums back in the nineteenth century. It was now a place to learn the secrets of the forest. The gardener strolled off as a train of primary school children departed the house on an adventure into the wild. Kerry Rolison was perched on a sit-on mower when the gardener found her. Slight and friendly, she greeted this stranger in her grounds with a gentle handshake. I started to explain my literary quest.

'Clare?' she guessed.

I was not the first visitor to Fair Mead. Iain Sinclair came here in July 2004 on the trail of Clare's eighty-odd mile walk from Essex back to his wife and children in Northborough, close to Peterborough. Sinclair had peered over the Suntrap's wall and been put off by the 'notice forbidding unauthorised entry'. But he had offered his own unique take on the transformation of Fair Mead asylum to Suntrap Field Centre:

Nature studies (woodcraft for recidivists and malefactors) have replaced the trade in lunatics (returned to their communities). Clare's fascination with creepy-crawlies, fungi, ferns, is now proposed as therapy for a sick city.3

It seemed a trifle hard on the primary school kids.

I followed Kerry to a first-floor open study room that was all glass and air, where she headed for a set of drawers and started to extract old copies of documents on Fair Mead and on Clare.

'Fair Mead became The Suntrap Convalescent Home, then a TB hospital and then a maternity hospital,' Kerry stated with some authority. 'You can imagine the lines of beds in here.'

I was busy flitting through the papers she had unearthed.

'They were all part of an exhibition put on some years back,' she explained.

There was a plan of the original Fair Mead House, described as 'A Private Establishment for Insane Persons, belonging to Dr Matthew Allen' and containing a dormitory, various bedrooms, a piggery and a separate cottage 'to be used occasionally for Noisy Patients'. An OS map of the immediate vicinity from 1870 showed St Paul's chapel and the chapel yard. Kerry dug deeper and handed over a copy of the asylum admission ledger for 1837, the year John Clare arrived.

'I can photocopy anything you’d find useful.'

When we left, children chatted excitedly in a neighbouring room; eight and nine-year-olds thrilled at a magnificently magnified beetle on a whiteboard. I clutched my batch of photocopies and followed Kerry downstairs. Outside, it was still glorious. Kerry had kindly offered to walk me the short distance along Church Road to the former site of St Paul's chapel. The chapel yard had been one of Clare's favourite haunts, a place where he had created many of his High Beach poems. One of the items I had tucked under my arm was a copy of a letter written by a Laurence Harrison-Young in March 1979. He recalled a double row of thorn trees that ran parallel to Church Road from Fair Mead House to the neighbouring asylum of Lippits Hill Lodge where Clare was housed when he finally broke from Essex in 1841. The purpose of the hedge was that Allen's patients 'could walk from one to the other without being seen by the public'. Harrison-Young remembered seeing part of the thorned hedge in 1920. I imagined Allen’s asylums, those grand old Victorian mansions for the mad, with their spiky shield to keep the sane from the insane.

Kerry asked about the work on Clare. I explained it was part of a broader project to track the paths of writers through the wilder reaches of Essex.

'It's a kind of literary psychogeography of the Essex countryside,' I added and started to wonder if that made much sense. There really weren't the words to describe the enterprise. Psychogeography had been born as an urban pursuit. What was its country cousin to be called? In this leafy border to London, the term still seemed just about to fit; especially when chasing a man as confused and tormented as Clare.

'My daughter's taking English at A level,' Kerry said. 'She's studying Clare.'

There was a pause.

'And doesn’t really like him.'

She smiled at the confession. Her daughter was at college in Walthamstow, just a twenty-minute drive south but a world away from the beeches of Epping Forest or the fen landscapes of Clare's birthplace.

'Perhaps he's a little too rural for her,' I wondered.

It was back to that old chestnut: the divide between the city and the country.

Kerry plunged into the shade of the trees to the east of Church Road. A reverent silence enclosed us.

'It's around here somewhere,' she said. 'Just past that stream, I seem to remember.' I followed her over the leaf litter, away from the road and into the wilder world of the wood.

'Ah, here we are,' Kerry declared.

A hollowed horseshoe in the forest floor revealed the plan of St Paul's chapel. Once hallowed ground, the site had been all but swallowed back into forest in the 140 years or so since the small church had been demolished. Three mossy bricks, half-hidden in beech leaf, were all the hard evidence of the original building. And yet there was a kind of distant hush as though some semblance of the chapel's presence remained. It was exactly that sense which I had come here to feel. I thanked Kerry again for all her help and bade her farewell.

I stood alone among the trees. Amidst these forest shades, Clare would have wandered, rhyming, versifying as he walked. Then he would have rested against some trunk of beech, hornbeam, oak and made his pencillings. I already knew that if I was to conjure something of the soul, the spirit of Clare, it was not simply a case of walking the land but of delving into the life, the soul, of the poet and those rhymes, verses that had risen from these fecund Essex soils.

∗

The week before, I had been in the British Library. Clare wrote very few poems in the first three years of his time in Essex. In May 1841, he was visited at High Beach by Cyrus Redding, who soon after published an account of his meeting with John Clare and a collection of some twenty poems the poet had recently written:

A few days ago we visited John Clare, the "Peasant Poet," as he styles himself, at present in the establishment for the insane of Dr. Allen, at High Beach, in Essex. We were accompanied by a friend, who had formerly known Clare. The situation is lofty; and the patients inhabit several houses at some distance from each other. These houses stand in the midst of gardens, where the invalids may be seen walking about, or cultivating the flowers, just as they feel inclined. The utmost politeness was exhibited upon our making our object known; and we were informed that Clare was in an adjacent field, working with four or five of the other patients. We accordingly proceeded thither, and saw the "Peasant Poet," apart from his companions, busily engaged with a hoe, and smoking.4

Cyrus Redding's accompanying friend found himself 'surprised to see how much the poet was changed in personal appearance, having gained flesh, and being no longer, as he was formerly, attenuated and pale of complexion'. Essex had been kind to Clare, though the poet expressed 'a great desire to go home', stating that 'his solace was his pipe – he had no other: he wanted books.' What books? Byron, he replies and Redding and his party 'promised to send that poet's works to him'.

The poems Clare handed over to Redding tell of his life in High Beach. They also tell of Clare's changing mood. The sense is no longer of melancholy at the ways of man but, like his earlier verse which had won the hearts of the London elite, joy at the ways of nature:

TO THE NIGHTINGALE

I love to hear the Nightingale –

She comes where Summer dwells –

Among the brakes and orchis flowers,

And foxglove’s freckled bells.

Where mugwort grow like mignonette,

And molehills swarm with ling;

She hides among the greener May,

And sings her love to Spring.

I hear her in the Forest Beach,

When beautiful and new;

Where cow-boys hunt the glossy leaf,

Where falls the honey-dew.

These first stanzas show Clare happily wandering his new world of the forest, apparently content enough passing his time in nature. He has reverted to those pastimes enjoyed as a child in Helpston: listening to birdsong; seeking out birds' nests:

I knew the sparrow could not sing;

And heard the stranger long:

I could not think so plain a bird

Could sing so fine a song.

I found her nest of oaken leaves,

And eggs of paler brown,

Where none would ever look for nests,

Or pull the sedges down.

The Essex woods provide a harmony for Clare. In 'Sighing for Retirement', he details his longing for the still of the countryside:

O take me from the busy crowd,

I cannot bear the noise!

For Nature's voice is never loud;

I seek for quiet joys.

He has that calm at High Beach:

And quiet Epping pleases well,

Where Nature's love delays;

I joy to see the quiet place,

And wait for better days.

It seems that by the spring of 1841, nearly four years after being admitted to Allen's asylums, Clare has found a peace of mind in Epping Forest. It is a world utterly contrasting with that of his beloved fenland, yet he has grown to love these woodlands too. He contemplates his time there, knowing that patience will be needed if he is to see the 'better days' of home, family and sanity.

Three sonnets in particular draw directly on the relationship Clare developed with the Essex landscape which nursed him to some form of serenity:

A WALK IN THE FOREST

I love the Forest and its airy bounds,

Where friendly CAMPBELL takes his daily rounds;

I love the break neck hills, that headlong go,

And leave me high, and half the world below;

I love to see the Beach Hill mounting high,

The brook without a bridge, and nearly dry.

There's Bucket's Hill, a place of furze and clouds,

Which evening in a golden blaze enshrouds:

I hear the cows go home with tinkling bell,

And see the woodman in the forest dwell,

Whose dog runs eager where the rabbit's gone

He eats the grass, then kicks and hurries on;

Then scrapes for hoarded bone, and tries to play,

And barks at larger dogs and runs away.

There is a spring to the tone of the poem which is resonant not only of the season, but the lightness of Clare's present mind. It is there in the playful charm of the woodman's dog. A bucolic tranquillity can be heard in the melodious mantra of the cow bells. Clare's love for this sylvan landscape is evident enough. When Cyrus Redding presented these poems to the public for the first time in The English Journal in May 1841, he recognised how this new world had altered the poet's temperament such that 'the wildness of Epping Forest has called forth his verse in its celebration'.5

Those sweet pleasures of forest life find further expression in a second sonnet:

A WALK ON HIGH BEACH, LOUGHTON

I loved the Forest walks and beechen woods,

Where pleasant STOCKDALE showed me far away

Wild Enfield Chase, and pleasant Edmonton;

While Giant London, known to all the world,

Was nothing but a guess among the trees,

Though only half a day from where we stood.

Such is ambition! only great at home,

And hardly known to quiet and repose.

I loved the Forest walk, and often stood

To hear boys halloo to their wilder sheep;

While quiet TURNER sat upon a hill,

And gentle HOWARD cut his sticks and sang.

The Sticker trailed her faggot on the ground,

And all the Forest seemed to live with joy.

Stockdale is an attendant. Turner and Howard are fellow inmates also enjoying their time at High Beech. Presumably the 'Sticker' is a local woman out collecting kindling. London sits at a safe distance between the trees. Cyrus Redding noted that 'some of the views from the Forest sweep over the Thames into Kent … all sufficiently remote'.6

In this third sonnet, a similar sentiment reigns. Again, it is on the natural wonders of the forest, rather than London, which Clare eulogises:

The brakes, like young stag's horns, come up in Spring,

And hide the rabbit holes and fox's den;

They crowd about the forest everywhere;

The ling and holly-bush, and woods of beach,

With room enough to walk and search for flowers;

Then look away and see the Kentish heights.

Nature is lofty in her better mood,

She leaves the world and greatness all behind;

Thus London, like a shrub among the hills,

Lies hid and lower than the bushes here.

I could not bear to see the tearing plough

Root-up and steal the Forest from the poor,

But leave to freedom all she loves, untamed,

The Forest walk enjoyed and loved by all!

London may be on the door-step, but it is the wild woods of Essex which have eased the poet's mind. Clare's only worry is that the forest should remain free for all, should be protected from the ravages of the 'tearing plough'. The verses which Redding published in The English Journal show a John Clare healthy and happy in his new world of Epping Forest; the themes of the poems reflect this contentment. His confinement is no longer a barrier to his poetry.

Yet not all Clare's words from his time in Essex tell such happy tales. 'Nigh Leopards hill stand All-ns hells' was written in early 1841 and makes up part of the Northampton Manuscript 8. It tells a quite different story. 'All-ns hells' were the three houses that made up Matthew Allen's asylums: Fair Mead House, Leopard's (Lippitt's) Hill Lodge, and Springfield Lodge. Robinson and Powell note, 'it was to Leopard's Hill that Clare was brought in June 1837'.7 It was from here that he would finally flee in July 1841.

Nigh Leopards hill stand All-ns hells

The public know the same

Where lady sods & buggers dwell

To play the dirty game

A man there is prisoner there

Locked up from week to week ...

Gone are the freedoms of the forest. Now there is only cruel confinement.

As I ploughed through Clare's works in the library, other verses centred on the landscape of Epping Forest came to light. That interest in Byron which Clare expressed to Cyrus Redding and his party on their visit to High Beach in May 1841 soon found expression. Clare's own 'Childe Harold' was written in the spring and summer of 1841, first at High Beach and then at Northborough following Clare's flight from Essex. Thoughts of Mary Joyce, Clare's beloved first love, weave throughout the work with nostalgic aching in lines like 'I've lost love home and Mary' (from 'Song a') where the loss of commas seems only to add to the sorrow and sense of bereavement, abandonment.8

In 'Song b' there is a glimpse of St Paul's chapel, one of Clare's favoured sites within the forest:

How beautiful this hill of fern swells on

So beautiful the chapel peeps between

The hornbeams – with its simple bell – alone

I wander here hid in a palace green

Mary is abscent – but the forest queen

Nature is with me – morning noon & gloaming

I write my poems in these paths unseen

& when among these brakes & beeches roaming

I sigh for truth & home & love & woman

A stanza later he returns to St Paul's:

Here is the chapel yard enclosed with pales

& oak trees nearly top its little bell

Here is the little bridge with guiding rail

That leads me on to many a pleasant dell

The fernowl chitters like a startled knell

To nature – yet tis sweet at evening still –

A pleasant road curves round the gentle swell

Where nature seems to have her own sweet will

Planting her beech & thorn about the sweet fern hill.

I looked up 'fernowl' in Webster's 1828 English dictionary and found 'Fern-owl, n. The goatsucker.' Under 'goatsucker' was the definition: 'In ornithology, a fowl of the genus Caprimulgus, so called from the opinion that it would suck goats. It is also called the fern-owl.' The goatsucker is now known as the nightjar – one of Clare's favourite birds.

Then I headed for lunch, chewing through an Irish lamb stew in the library restaurant while musing on Clare. He looked on birds from so kindred a position; always gently nurturing the creatures around him, never peering through the lens of a powerful monocular. He was a grandfather of ornithology with much to teach. I'd been reading his 'Nature Notes' written some years before High Beach. He wrote passages on ants, bats, hawks and sparrows with a gentle affection for the creatures that was born of endless hours of shared-time spent with them in nature. But it was his description of 'The Butter Bump' which had most captivated me:

This is a thing that makes a very odd noise morning & evening among the flags & large reedshaws in the fens some describe the noise as something like the bellowing of bulls but I have often heard it & cannot liken it to that sound at all in fact it is difficult to describe what it is like its noise had procurd it the above name by the common people the first part of its noise is an indistinct sort of mattering sound very like the word butter utterd in a hurried manner & bump comes very quick after & bumps a sound on the ear as if echo had mocked the bump of a gun just as the mutter ceasd nay this [is] not like I have often thought the putting ones mouth to the hole of an empty large cask & uttering the word 'butter bump' sharply would imitate the sound exactly ...9

Written with his breathless prose, Clare had transformed the call of the bittern into a 'butter bump'. Not only did the term hold a rustic beauty, it was a more precise replication of the male bittern's call than the rather prosaic and unimaginative 'boom' used by today's bird watching fraternity.

∗

A week on, I sat at the foot of a giant oak just to the east of where St Paul's chapel once peeped 'so beautiful ... between the hornbeams'. The tree had a diameter on the ground of some five foot or more. In Clare's time, it would have been one of those oaks of 'Song b' which 'nearly top' the chapel's 'little bell'. Here was a physical continuity across the years, a tangible bridge to Clare. I touched the oak with due reverence and tucked down at the tree's base, just like Clare, 'hid in a palace green'. It had been easy enough even today to step a few feet from the tarmac of Church Road and feel enclosed by the forest, hidden away. There was the covering of trees, a cloak of leaves to screen from others' eyes. There was the still of nature. Left alone in the space where the chapel would have been, I had stepped gently around the site, striving to see the pales of the picket-fence, the 'little bridge with guiding rail' over the brook. It was all long-gone. Yet the forest remained and so did some vestige of what Clare expressed in 'Song b': 'A pleasant road [Church Road] curves round the gentle swell, Where nature seems to have her own sweet will, Planting her beech & thorn about the sweet fern hill.'

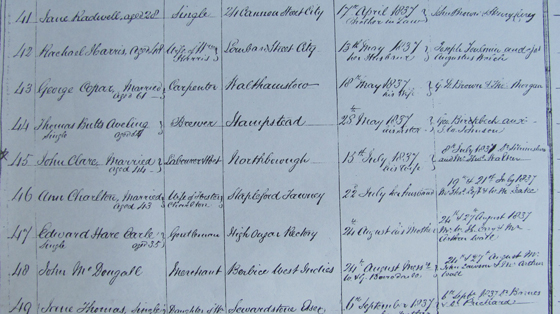

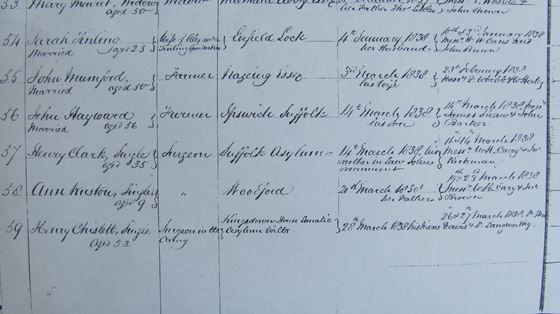

At the foot of Clare's oak I rested, dug my hand into the rich humus and leant against the ribbed bark, settling into the soil. For some time I simply sat and let the forest recover from my intrusion. Then with quiet hands I opened the batch of photocopied papers, and looked over the copy of the admission ledger for patients accepted into Dr Matthew Allen's High Beach asylum in 1837. When Clare arrived in July that year there were forty patients in Allen's asylums: seventeen were 'curable', twenty-three 'incurable'.10 John Clare was numbered patient 45. He was noted as married and aged 44. His 'Occupation or Profession' was listed as 'Labourer & Poet'. The register also held the details of Clare's fellow patients. I scanned for the names of Stockdale, Turner and Howard mentioned in the poem 'A Walk on High Beach, Loughton' and found patient 56: a John Hayward, aged 56; a farmer from Ipswich admitted on 14 March 1838. Could Hayward be the 'gentle Howard' who 'cut his sticks and sang'? It seemed impossible to know. Yet later that day, I read a letter from Clare, sent to Matthew Allen after he had 'escaped' Essex. It had been written in the spare spaces of the Lincolnshire Chronicle and General Advertiser for Friday, 27 August 1841. A postscript from Clare asks that 'best respects' be sent to 'Campbell & Hayward & Howard at Leopards Hill'.11 Here was the answer. Hayward was not Howard, but evidently John Hayward too had become a friend of Clare in their time at High Beach. I continued to scan the admission ledger. Two names down from Hayward's entry, my eyes stopped: 'Ann Ruston, single, aged 9'. She was from Woodford, just down the hill, and had been admitted on the authority of her father on 20 March 1838. A young girl; a child; a daughter.

I thought of my own daughter, Eva, who that morning had begged to join me on a trip to the woods. She had picked out one of the shortbread biscuits she had made and handed it to me for my lunch. It was heart-shaped with a Smartie in the middle. I thought of Clare sat here a century and an half and more ago, thinking of his children so many miles away. I thought of Ann Ruston. How bad had her madness become that her father had committed her at the age of nine? I had never considered that there would be children held in Allen's asylums. Somehow I had always pictured a handful of lost souls wandering the paths of the woods, gently gardening or sat upon scattered benches letting the forest peace seep into their feverish minds. Of course, there would have been the patients with more severe mental illness; the screaming Susans straitjacketed, hidden from the public eye, their world confined to walls. Yet I had never envisaged children in High Beech. There were so many tales untold. What had happened to Ann Ruston, 'single, aged 9' in those years that Clare passed in Essex? What of her father who entrusted her to Springfield House just a couple of miles north of his home in Woodford? These are histories unknown.

I rose and started walking east, away from St Paul's chapel, soon discovering Clare's 'brook without a bridge' and followed it as it wound south, down the hill. A footpath which ran beside the stream had been rutted with tyre tracks from off-road bicycles. Clare's feet would often have been found on this path in those four years he passed in the forest. I followed them until the woods opened to air, to a field of grass at Fairmead Bottom and to Fairmead Pond where three mallard drakes floated serenely on the dark surface. By the pond I paused and knew that here the poet must have sat on burning summer days, feeling the delicious cool of the water. My way had been a meander dictated by flowing waters which had only halted where the brook did - here, at the bottom of the hill.

There was little intrusion from the present. Some dogs barked in the distance. I could hear the roar of cars on the Epping New Road but not see them. I headed back up Fern Hill, by another pathway east of the brook, parallel with Fairmead Road, glad to plunge back into the cover of trees as a woman appeared pushing a pram, her pit bull running beside her. In the forest, I could be as Clare, alone and free to wander 'in these paths unseen'. That morning I had been talking to Kerry Rolison at the Suntrap of the urban wanderer, the flâneur. Now I was a rural rambler. Though the city had pressed down on Epping Forest in the decades since Clare, this was certainly a world dominated by a sense not of mankind and its monuments on the earth, but by nature. My wander was a stroll not a march through the forest. If I was to achieve any sense of feeling for the atmosphere that engendered Clare's High Beach poetry, it would arise from adopting his way through the trees. Up the contours of Fern Hill I noted the muscular ribbing of the hornbeam, ran my hand along the smooth skin of beeches and slipped away from a sign that warned of fly-tipping. At the cross roads there was a sudden shock of humanity and the incongruity of arriving at a noisy crowd of bikers sat outside a tea stall. Furtive now, wary of mankind, I nipped back into the comfort of the woods.

Beside an oak some thirty yards away was a sight instantly shocking. It was a site of death, I thought. Faded flowers in their plastic shrouds, planted beside a tree, as seen on all the roads, emblems to crash sites, lives lost. And here lay a body in the forest. I could not stop myself from walking over, crunching leaves like gravel in a churchyard leading to the fresh grave. Yet it was merely rubbish: a bag of plastic; drinks cartons; tin cans. Fly-tippings. The vision across the forest floor was enough to spike my thoughts with those of bodies in the woods, with modern tales of the forest as a dump not for the insane, but for dead lovers, discarded gangsters. In strips the forest is transformed. There is a fringe beside the roads, the tea stalls, the bikers, where the litter of humans infiltrates the woods, puncturing the pristine pattern of nature with alien forms. There are few bright colours, smooth shapes in nature. In this fringe, a red can shines out from the beech leaf floor. At first glance it is a fly agaric, the brilliant red hue of Amanita Muscaria, much beloved by the shaman: the Alice-in-Wonderland mushroom. But this is no birch wood, no Siberian steppe, no magical fantasia. It is no mushroom at all, just a Coke can dropped, discarded. Remnants of polystyrene cups, crisp packets, drift out from the bins, from the places humans gather daily in the woods. Lager cans, Bacardi Breezer bottles tell of nightly trysts. Step further into the depths of the woods and this flotsam fades. But in this forest fringe, there are no rising resonances of poet's footfalls.

Startled by the present, by the presence of people, I veered further into the forest until two vast pale trunks of trees rose like a gateway to another world. They were beeches. Ghost beeches. Each towering pillar was an ancient arch over a path to a hidden place. I stood between them, stepped beyond and felt the present slide. On my neck I found a yellow caterpillar. I stumbled on until a sea of silver birches surrounded me; each was mere inches across, yet rising forty, fifty feet into the forest rooftops. I plunged in. A feeling of submersion started to take a hold. I halted, stared at the swaying limbs and knew I was lost at last in the forest.

I emerged back beside Dairy Farm to the startling colours of rhododendrons. A bus full of schoolchildren from the Suntrap Field Centre laboured up Church Road. I traced a path back to what was once the chapel yard, returned to Clare's oak and sat, listening to the birdsong. There, in my bag, was the perfect, heart-shaped shortbread Eva had made and given to me this morning. I ate it, leaving the red Smartie for her to savour later in the day, and watched a treecreeper spiral up an oak. In that still which falls only when the footsteps cease, when the creatures of the forest venture forth, there came that self-same longing felt long years before by Clare: a 'sigh for truth & home & love ...'.

Extract taken from forthcoming book: Out of Essex: Re-Imagining a Literary Landscape (due January 2013).

Notes

1 Written at High Beach, Essex - probably in 1841. Much of Clare’s verse has a personal approach to punctuation and spelling generally left untouched by his editors. I have adopted the same hands off approach to all his work quoted here.

2 Benj. P. Avery, 'Relics of John Clare', The Overland Monthly, x (1873), 134-41 (pp. 138-9).

3 Iain Sinclair, Edge of the Orizon (London: Hamish Hamilton, 2005), pp. 129-30.

4 Cyrus Redding, 'Clare, the Poet', The English Journal, 1 (Jan-June 1841), 305-9 and 340-343 (p. 305).

5 The English Journal, 29 May 1841, p. 340.

6 The English Journal, 29 May 1841, p. 341.

7 The Later Poems of John Clare: 1837-1864, vol 1, edited by Eric Robinson and David Powell (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1984), p. 37.

8 The Later Poems of John Clare, p. 44.

9 The Prose of John Clare, edited by J. W. and Anne Tibble (London: Routledge, 1951), p. 197.

10 Jonathan Bate, John Clare: A Biography, (London: Picador, 2004), p. 428.

11 The Letters of John Clare, edited by Mark Storey (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1985), p. 650.

About the article

Relics of John Clare

'Relics of John Clare' is an extract taken from Out of Essex, an exploration of literary wanderings in the county, due for publication in January 2013.

This book tracks the paths of those literary figures who have ventured into the wilder parts of Essex. Some are illustrious names: Shakespeare, Defoe, John Clare, Joseph Conrad, H. G. Wells, Arthur Ransome. Others may be lesser known but here are well remembered: Samuel Purchas, Sabine Baring-Gould, Margery Allingham, J. A. Baker.

In ten chapters James Canton crosses five centuries into the furthest reaches of the county in search of writers and what can be seen of their work today. J. A. Baker follows the peregrines along the Chelmer valley to the Blackwater estuary at Maldon. John Clare wanders the hidden pathways of Epping Forest scribbling poetry while Arthur Ransome sails around the islands of the Hamford Waters. William Shakespeare appears in the woody glades beside Castle Hedingham, Joseph Conrad stares across the Essex marshes at Tilbury to the Thames, while Sabine Baring-Gould's Gothic heroine Mehalah lives upon a lone muddy stretch beside Mersea Island, where Margery Allingham sets her first tale – of smuggling and murder; Daniel Defoe recounts the horror of the ague on the Dengie Peninsula; H. G. Wells writes a tale of the First World War from his home at Little Easton. Samuel Purchas tells such seafaring tales from his Southend vicarage as to inspire Samuel Taylor Coleridge to write Kubla Khan.

Combining detailed literary detective work with personal responses to landscapes and their meanings, James Canton offers a fresh vision of Essex, its cultural history and its living legacy of wilderness and imagination. In his foreword to Out of Essex, Ronald Blythe describes the book as full of 'fresh and stimulating encounters with literary Essex ... a pleasure to read'.

About the author

James Canton

James Canton teaches at the Department of Literature, Film, and Theatre Studies at the University of Essex. He has taught the MA in Wild Writing at the University of Essex since its inception in 2009, exploring the ties between literature and landscape. His book From Cairo to Baghdad was published in 2011. Out of Essex: Re-Imagining a Literary Landscape, a collection of writing inspired by rural wanderings in the county, is forthcoming in January 2013.

Links

James Canton

James Canton's profile - Department of Literature, Film, and Theatre Studies at the University of Essex

MA Wild Writing: Literature and the Environment - Department of Literature, Film, and Theatre Studies at the University of Essex